|

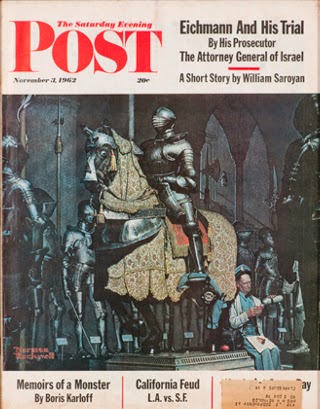

| "Lunch Break with a Knight" by Norman Rockwell, 1962 |

An early clue that I wouldn't survive architecture school came when one of my studio professors scoffed at the skills of populist painter Norman Rockwell.

"That's not art," this particular professor bellowed to us second-year students, perched on metal stools beside our white drafting tables. Rockwell wasn't a good artist, supposedly, because he was too literal. Good art, according to our professor, should be different things to different people.

Reality is relative, right?

Sure, I thought, sometimes art can be interpreted in multiple ways. But did that mean Rockwell was a bad artist? Not in my book.

This was one of the many disagreements I had with how my architecture professors wanted their students to view the profession, and our world in general. Suffice it to say that I never obtained a degree in design.

As far as Norman Rockwell is concerned, however, I'm not sure how anybody can argue that his art isn't compelling. Take, for example, what's probably my favorite Rockwell work, "Lunch Break with a Knight". He created it for the November 3, 1962 edition of the Saturday Evening Post, a popular magazine in his day. And while at first glance, it looks like a literal depiction of a museum security guard having a break in a darkened gallery featuring suits of armor, there's a lot more going on that people like my architecture professor must be missing.

The setting for this painting is attributed to the former Higgins Armory Museum in Worcester, Massachusetts, whose collection has since been assumed by the Worcester Art Museum. But we don't really need to know the setting from which this tableau has been adapted to understand that body armor has had a long and colorful history. And that the best armor was usually worn by the most powerful warriors. And that masculinity, for all of its pretense of aw-shucks simplicity, can be downright audacious in the gaudy spectacle some men make of themselves. Just look at all of the shiny metal that was worn into battle after being perforated with intricately-designed embellishments, polished, adorned with plumes, and strapped with leather and fabric.

Oh, the poor horses that had to carry those men, clanking about in iron suits that must have weighed a ton! And even some of the horses were sheathed in matching metal shields. Towards the latter part of the Middle Ages, some armies were actually breeding special horses that could remain exceptionally agile under such a burden.

And how majestic these horses and riders must have looked! How invincible they must have felt! These were the rock stars of their day; the men for whom damsels swooned, and to whom kings apportioned property. Heroes, conquerors, with the physical strength to carry all of this armor and be mobile enough to be able to protect themselves. Wimps like me couldn't possibly hope to find any greater satisfaction wearing such a get-up than standing up and not tipping over.

Eventually, as guns and bullets replaced arrows and swords, armor plating became ineffective. By the turn of the 18th Century, such armor had become more ceremonial than functional, and was used more by commanders and royalty to monitor battles, than by foot soldiers doing the actual fighting. By the time of America's Civil War, body armor had become so obsolete, neither the North nor the South provided any to their soldiers, although some desperate men on both sides are reported to have personally bought pieces of body armor for themselves. Interestingly, across the world in Japan, this was about the same time that body armor had its last gasp for Samurai warriors as well.

But all of that is ancient history, right? How does Rockwell's painting relate to us today? After all, good art is supposed to be trans-generational and cross-cultural, right?

Well, let's look at Rockwell's composition for this scene, shall we? We've got a darkened museum gallery, with one armored horse and rider illuminated in the middle, suggesting that the museum is closed for the day, with at least one spotlight left burning to help the watchman do his job. We also see this watchman's black, industrial-sized flashlight - there, in the pocket of his jacket, that he's carefully draped over the foot and stirrup of our gallant suit of armor, and the finely clothed horse.

The watchman's cap is tilted back, presumably after he's rubbed his forehead in a relaxing gesture to indicate that all is currently right with his world. He's got his black metal lunchbox at his side, and he's seated on the display, comfortable and cozy. His napkin is neatly unfolded into a perfect square on his lap, and - instead of his healthy apple! - he's got a delectable slice of chocolate-frosted cake he's getting ready to enjoy -with a steaming cup of coffee from his Thermos.

Okay - so it's a pretty typical depiction of a normal, working man's coffee break. Which is precisely the juxtaposition Rockwell wants to portray against the backdrop of such armored grandeur. Imagine the mortal battles through which all of this majestic armor has endured! How about the mighty men of valor who won wars - or lost their lives - wearing all of this hardware? Can you hear the noise and chaos of conflict, with clanging swords, stomping horses; the screaming and yelling of strong, muscular men fighting to the death?

Meanwhile, our docile watchman doesn't appear to have a weapon of any kind, unless you count that hefty-looking flashlight. He's got no gun, or bullet-proof vest, and why should he? What's in this museum that's worth his life? Everything is either insured, or so famous that nobody could steal it and hope to sell it on the black market. This man's presence in this closed, dark museum is more of a deterrent for bumbling vandals or mischievous teenagers than a front line against a desperate aggressor, or a pursuer of a hardened criminal.

And what of all these suits of armor, anyway? Sure, we see little placards at the feet of every display, where museum officials have provided some information about who might have worn each particular piece, or when it was used. But who among us would otherwise know that information, or the names of the men who lived and died in these suits? In their day, they were men of value, importance, intrigue, and prestige. But today? We look at their armor and briefly marvel at how primitive warfare used to be. Today, our state-of-the-art Kevlar and other sophisticated, high-tech fabrics that serve as modern body armor function amazingly well, even if they don't look as grand as these suits of armor.

Indeed, it's the irony between grandeur and humility that embodies Rockwell's message with this painting. Grandeur of the past, and forgotten names, contrasted with the humility of a night watchman, taking his coffee break, and a brief, relaxing respite at the feet of armor that once stood between life and death for the person wearing it. And speaking of feet, a full graphic of this painting shows that the watchman is a rather short fellow, seated on the pedestal with his feet dangling up off of the floor. Kinda shrimpy and impotent, right?

Okay. So... here's where Rockwell's painting hits home. Four hundred years from now, who's going to remember your name? How antiquated is what you're wearing right now going to look? How significant will what you're doing right now for a living have been, even if you think you're saving your country from defeat?

Maybe people who don't think such paintings are art simply don't like what such paintings are saying.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for your feedback!

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.